Cormac McCarthy and the Struggle To Separate Art From the Artist

A novelist and McCarthy specialist explains his inner debate following the recent revelations about the storied author.

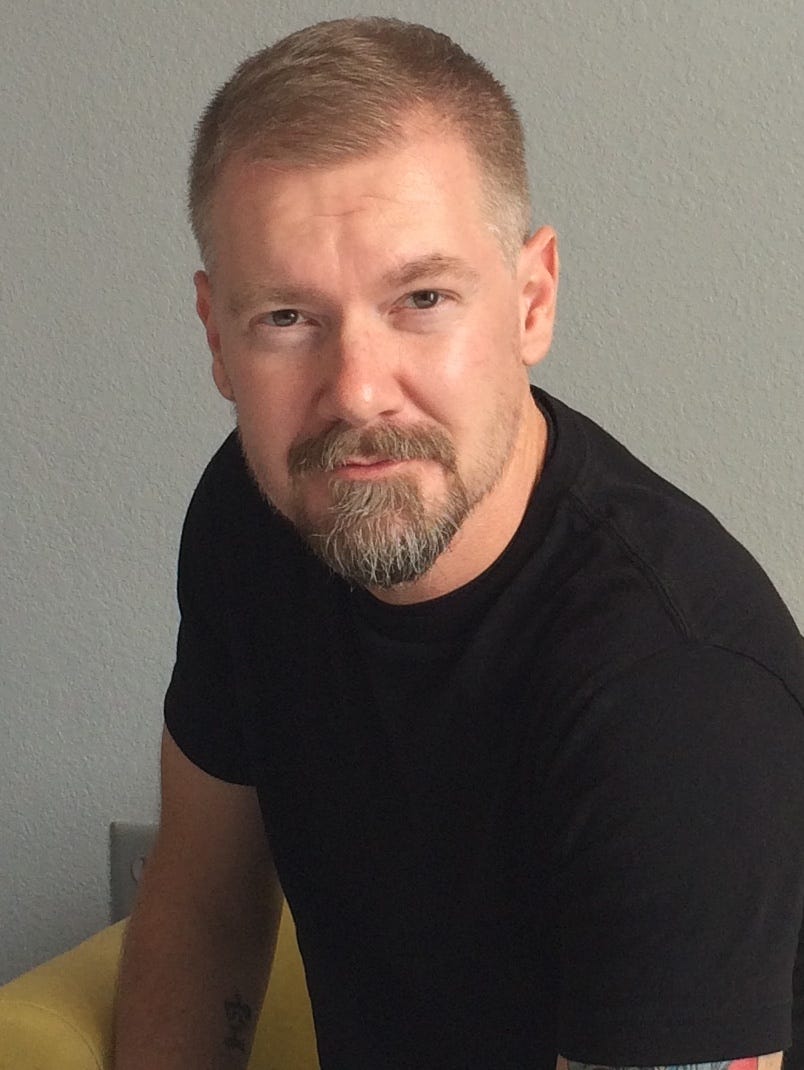

Aaron Gwyn, a novelist and English professor at University of North Carolina at Charlotte, was not always so interested in the written word.

Growing up in Oklahoma, he was far from a star student. He had middling grades in high school, but when he arrived in community college, he found professors who encouraged him to write.

In the mid-90s, he decided to pursue his Master’s at Oklahoma State University (OSU). It was there that he first encountered the work of Cormac McCarthy.

He decided to read All the Pretty Horses, which had just won the National Book Award.

“I read it, and I liked it OK, it didn’t blow me away,” he confessed in an interview.

But while at OSU, he crossed paths with Brian Evenson, a novelist and an academic who had long studied McCarthy’s work. He was particularly entranced by Blood Meridian, McCarthy’s 1985 novel.

Gwyn picked up the book. At first, he was taken aback by the violence in the text.

“So I kind of struggled my first about three-quarters of the way through it, but in that last 50, 70 pages when the novel really just completely cooks up the boiling. I was like holy crap, this is the most incredible thing I’ve ever read,” he said.

He fell in love with McCarthy’s use of language. In the years since, he devoured the late author’s texts. After getting his PhD at the University of Denver, he started teaching his books — something he’s now done for over two decades.

Every semester, he would teach at least one McCarthy book. He also started up a Substack and YouTube page where he analyzed his body of work. He became so known for his analysis that in the June of 2023, when McCarthy passed away, Gwyn wrote an obituary for The Spectator.

While Gwyn never met McCarthy in person, the impact he had on his life was unmistakable.

“He’s had about as profound an effect on me that a complete stranger could possibly have,” Gwyn told me. “And because I never met him, I had that uncanny feeling that you can have with writers that you really adore…where you feel like you know the person in a really intimate way even though you’ve been interacting with them entirely through their novels.”

That’s why a recent Vanity Fair article on McCarthy hit Gwyn like a sack of bricks.

“When I first read the article…my heart sank”

In late November, Vanity Fair published an article telling the story of a woman named Augusta Britt.

Britt explained to journalist Vincenzo Barney that she had met McCarthy when she was 16 and he was 42. As someone who was in and out of foster care, she didn’t have a stable family around to take care of her. McCarthy ended up playing a huge role in her life instead.

McCarthy began a romance with her while she was still a teenager and him a middle-aged man, and he even transported her away to Mexico at one point. He did all this while betraying the trust of his wife and a child of his own.

“When I first read the article…my heart sank. I didn’t want it to be true because [of] the way I feel about McCarthy,” Gwyn confessed to me.

He discussed the story with his girlfriend, who has two daughters. One of those two daughters is 10.

“She was like, Aaron, 16 years old, that’s only six years older than, and she said her daughters name….it just disgusted me,” he reflected.

He decided to take the difficult step of ending his Substack series about McCarthy. He also chose to make all of the posts available for free; any revenue he continues to generate will go directly to the Center for Missing and Exploited Children, a nonprofit that helps kids like the younger Britt.

He doesn’t see himself teaching about McCarthy again in his literature classes any time soon. He’s not sure what he will do with the Substack going forward, but he expects to post lectures on other authors on his YouTube.

In taking these steps, he didn’t see himself as telling other people how they should think about McCarthy going forward.

“I’m not saying McCarthy should be cancelled. I’m not saying his books should be unpublished. I don’t even know if such a thing is possible. I’m not telling anyone else what to do,” he said. “I’m not saying people should stop reading his work. I’m not saying any of that. All I’m saying is, I’m not going to continue making money off writing about him. I don’t feel it is moral to do so — or something, it’s not something to do so. I just felt wrong about it.”

In processing his response to the McCarthy news, Gwyn shared his wider theory about human behavior.

"I’m of the opinion that most of the important things that we do or the significant things that we do as people have very little to do with reason or any kind of conscious, cognitive analysis or whatever,” he said. “I think we make the most important decisions we make based on our intuition, our gut, our feelings.”

Blurring the distinction between an artist and their art

Gwyn’s response to learning about the flaws of a man he had spent his entire professional life admiring was common among McCarthy fans.

Many readers on the McCarthy subreddit, where thousands of fans congregate to discuss his literature, found themselves alarmed about the revelations found in the Vanity Fair piece.

If you’ve watched as other fandoms have had to learn unsavory details about the artists who gave them so much joy throughout their lives, you might experience a bit of déjà vu reading through the forum’s discussions on the article.

Gwyn acknowledged that this is a debate that is common in the literary and arts worlds.

“It’s a perennial conversation we have about people who make beautiful things and then the people themselves. I don’t claim to be any paragon of virtue or anything else. I love Hemingway. I love Faulkner,” he said. “Both of them did scandalous shit. That hasn’t diminished my love of their work.”

But a couple of factors make the revelations about McCarthy weigh heavier on Gwyn.

“[Hemingway and Faulkner] both died 10 years before I was even born. And I didn’t read them until my 20s and 30s. Well, yeah, they did scandalous shit,” he said. “They’re from a long time ago. But McCarthy was a contemporary!”

There’s also the fact that the Vanity Fair article suggests that McCarthy’s experiences with Britt served as inspiration for the stories he told in his novels.

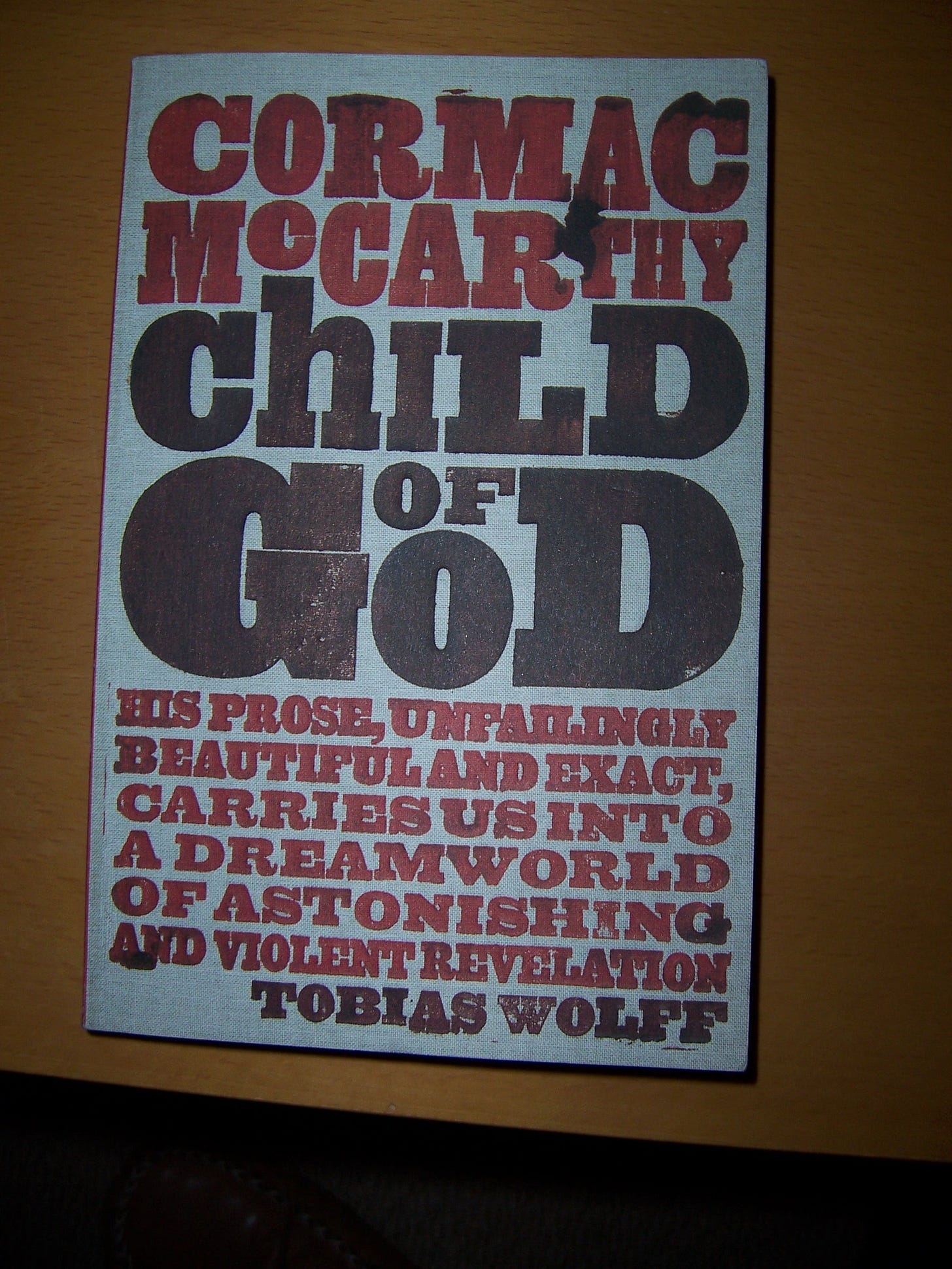

“I don’t that the books are evil. But he feels like he is channeling some part of that — because it’s all over his work. Child sex crimes, sexual assault against children, underage improper relationships, illegal relationships,” Gwyn explained. “It’s in Suttree, it’s all over Blood Meridian, it’s in the third book of the border trilogy, it’s in No Country for Old Men, pedophilia and pederast are a theme in The Road. And then his final works are about a brother who’s in love with his underage sister and how that ruins her life and his life.”

He can no longer see McCarthy as a moral man wrestling with evil. The stories now carry a different aura.

“All that stuff gets seen through a different lens, for me at least,” he said.

Grappling with good art from flawed artists

Unlike Gwyn, I have no deep connection with McCarthy’s work. I’ve seen a few of the film adaptations of his novels, and I’ve enjoyed them. He was clearly a talented writer who knew how to dive deep into the bowels of the human condition and hold up a mirror to our ugliest impulses.

Were some of those images in that mirror reflections of McCarthy himself?

For Gwyn, that possibility has led him to virtually eliminate his writing and teaching about McCarthy, a dramatic move given how important the author was to his personal career.

I have no problem continuing to enjoy McCarthy’s work, whether that means picking up a copy of one of his novels or watching future film adaptations (a Blood Meridian film has been planned for some time, but it’s not clear whether the Vanity Fair article will derail it.)

But it would be too flippant of me to tell Gwyn or any of McCarthy’s ardent fans that they should simply separate the art from the artist. While that’s generally my approach to these controversies, it’s not responsive to the needs of the thousands who read Barney’s article and have been struggling with their inner turmoil.

They say we should never meet our heroes because they can’t possibly live up to the image we’ve created of them in our heads.

But for Gwyn and millions of others like him, public figures play a role that is far greater than that of someone who simply put together a product you like — after all, would anyone ever say they felt uncomfortable sitting in a chair constructed by someone of low character?

Instead, public figures like Michael Jackson or Bill Cosby enthralled millions of people who saw their talent and good deeds as an inspiration. Every 90’s kid knows someone who would copy Jackson’s moonwalk; in the days before his abusive behavior was revealed, Cosby was seen as a hero to millions of minorities who could finally point to the example of a patriarch on TV who proved that a good middle class father and role model needn’t be white — he was even called “America’s Dad.”

I can’t see myself ever walking away from a work of art because of the sins of the artist. I’m still watching and enjoying the anime “Rurouni Kenshin,” for instance, despite its creator being charged with possession of child pornography.

At the same time, it would be ignorant for me to dismiss the torment people feel when they see their heroes falter. The relationships we form with those who fill our imaginations as Great Men and Women are sincere. If we truly feel connected to the authors who write the words that leap from page to imagination, then we have to be able to feel disappointment and hurt as well.

Our connections to each other are hardly just based in love and adoration; true human connection means falling with our heroes just as it means rising. In that sense, Gwyn’s response to learning an ugly truth about a man he spent his life looking up to may be the most human at all. If there’s anything McCarthy’s work is about, it’s that evil coexists with us in this mortal plane. Ignoring it is ignoring our reality.

I read McCarthy's Blood Meridian and the Border Trilogy decades ago and didn't really appreciate them. I'm embarrassed to admit I read them because I felt I should rather than for any literary value. After rereading them recently (along with The Passenger and Stella Maris and his other novels), I now have a completely different take on McCarthy and a much greater appreciation for his genius. I was surprised by the Vanity Fair article, but it hasn't dampened my admiration for McCarthy's writing. I'm not sure why. Maybe its because regardless of reading most of novels and knowing some of his background, I don't believe I can say I knew the man. I couldn't possibly say I understood him. (I have friends I've known for 50 years and still can't say I understand everything they do or have done). The extreme violence in McCarthy's novels always made me wonder about what are the inner workings of a man who can create, IMO, such graphic depravity. But it didn't stop me from admiring his writings. This latest revelation only reminds me how complicated people can be, and do we ever really know anyone.

Very thoughtful of you as usual. I especially liked this:

"If we truly feel connected to the authors who write the words that leap from page to imagination, then we have to be able to feel disappointment and hurt as well."

From now on I am going to be more respectful of people's feelings about their favorite artists. Thanks!