DEI Is a Failure Because the Civil Rights Movement Wasn’t About Elite Diversity

The tide is turning against modern diversity bureaucracies. But that's not necessarily bad news for progressives, at least if they believe in the goals of the civil rights movement.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) is having a bad week, as President Donald Trump has enacted an executive order that requires his administration to crack down on and remove diversity-oriented offices and policies across the federal government.

To many liberals, Trump’s order is distressing.

“I have to assume that ‘pursuing DEI efforts’ means hiring anyone who isn’t a white man?” asked The New York Times’s Jamelle Bouie about the administration’s new initiative to crackdown on DEI.

Indeed, the term DEI has at times become a sort of racist shorthand for corners of the online far-right, where people who in some cases were elected to office by the voters are derided as DEI hires simply because they’re nonwhite Democrats.

But not every critic of DEI is motivated by white resentment. Many people criticize these programs because they have little positive impact on diversity, anyway, and there’s a bunch of evidence that diversity trainings can actually make people more prejudiced.

The outcomes of Trump’s maneuver, however, remains to be seen because the devil is in the details.

Does removing DEI from the federal government mean eliminating potentially discriminatory programs? Or will the order end up throwing out the baby with the bathwater as it guts organizations that do have some proven benefit, like government teams that help protect the rights of disabled employees?

I would argue that the anti-DEI efforts we’ve seen pop up across the country over the past few years are capable of doing both things, and only time will tell what the Trump administration ends up achieving with its new anti-DEI directive.

But something is lost in this debate, where you have conservatives on one side railing against programs and practices they believe discriminate against white men and promote mediocrity and liberals on the other side defending DEI as an extension of the civil rights movement that guarantees the rights of minorities.

The reality is that DEI is only tangentially related to the rights and opportunities of minorities. The civil rights movement was not about diversifying corporate or government offices with a few black or brown faces in places of power.

It wasn’t about diversity trainings where employees roll their eyes as someone hired by HR lectures them for three hours about their privilege.

It was about redistributing power to the masses of people who don’t have it, including white people.

The civil rights movement was focused on the disadvantaged — including white people

We’ve all heard the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s famous quote from the 1963 March on Washington: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

It’s possible that no single utterance from King has drawn as much acclaim or is as popular among the American public. And that’s for good reason: it summarized the failings of American prejudice — assuming that someone had a certain character simply due to the shade of their skin was deeply unfair to African Americans and much of the past 60 years of American history has been dedicated to undoing this mindset.

But the emphasis on this quote also serves to mislead people about what the Civil Rights Movement was actually hoping to accomplish.

To bring us back to their goals, I want to turn to a televised panel that included King and many other civil rights leaders.

In the spring of 1963, a group of civil rights leaders joined National Educational Television (which later became the Public Broadcasting Service) to discuss the goals of the movement ahead of the historic march.

David Hoffman uploaded the full segment here, which is worth watching.

But I want to zoom in on what some of these civil rights leaders told the audience.

They spent little to no time discussing the need to train racist white people out of their attitudes. They didn’t talk about how they pined for a black woman as press secretary at the White House.

Instead, they talked about the needs of ordinary people who were being denied the opportunity to live decent lives.

James Forman, who was an officer in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, wanted the president to visit with the poor in Mississippi.

“I don’t think he has any conception, any visual conception, intellectually he knows the suffering that’s going on there — but just to see some of these shacks that people are living in. It’s frightening in a sense,” he said.

James Farmer, who served in the Congress of Racial Equality, pointed out that bitter poverty existed in the North.

“I think the President ought not only look at the housing in Mississippi, I think he ought to look at the slum tenements in Harlem, and in a hundred Harlem’s across the country. Indeed, we might say that people are not only being bitten by dogs in Birmingham…but by the rats in the slum tenements,” he said.

This prompted King, who was sitting with the leaders, to make his call to the nation, saying we needed to develop a program “to lift the standards of the Negro and get rid of the underlying conditions that produce so many social evils and develop so many social problems.”

Whitney Young, of the National Urban League, called for a “domestic Marshall plan,” referencing the massive aid the United States gave to Europe after World War II. Part of his proposal was “better schools and better teachers.”

Roy Wilkins, of the NAACP, also clarified that “we’re not asking them to skip over white people or deny white people their chance” when it came to the building of these programs.

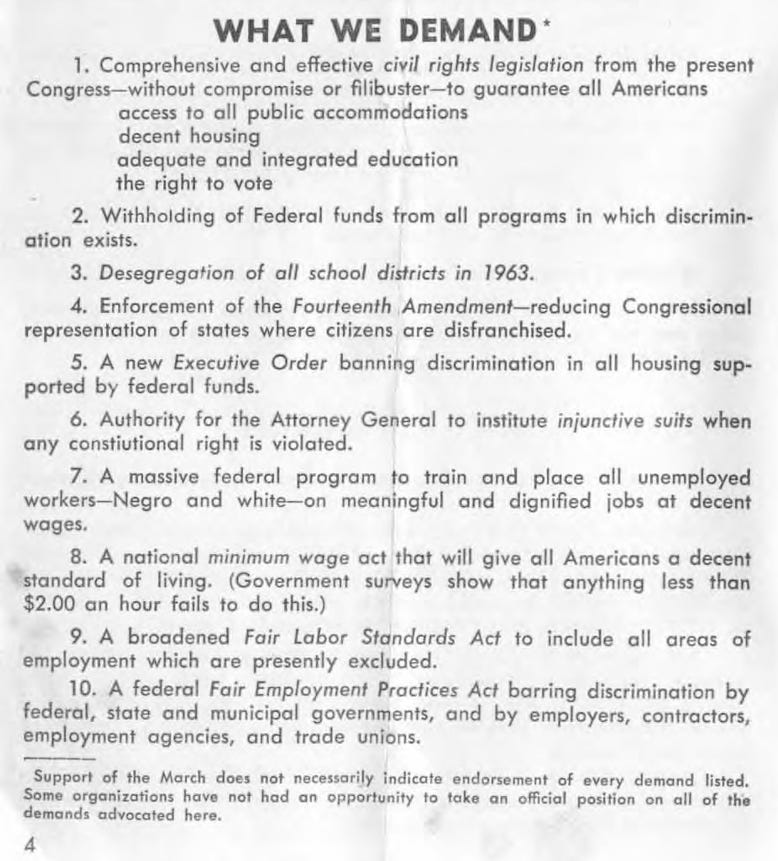

If any of this surprises you, you might revisit the 1963 march. Its full name is rarely used. It was called the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.”

A couple things might stand out from the ten demands presented at the demonstration. One, every demand centered on the needs of ordinary people — like black people forced to live in slums. Second, the demands also included addressing the needs of white people; the federal jobs program for the unemployed specifically called for assisting people “Negro and white”:

It can hardly be a surprise that King spent the last years of his life sponsoring a “Poor People’s Campaign.” While some advocates splintered off into black nationalism, King kept the faith, proposing a “Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged” to aid the white and black poor alike. Many of these demands from King and the Civil Rights Movement remain unfulfilled, yet none of them revolve around diversity programming.

After King’s death, his close adviser Bayard Rustin spent years arguing against black nationalists who had retreated to universities and replaced electoral politics with the warm embrace of critical theory and endless liturgy about race and racism.

In a scathing essay called “The Failure of Black Separatism,” he held nothing back describing the proliferation of “black studies” programs that aimed to segregate black students away from the rest of society and did little to threaten the status quo:

Yet now black students are preparing to repeat the errors of their white predecessors. They are proposing to study black history in isolation from the mainstream of American history [….]

Thus faculty members will be chosen on the basis of race, ideological purity, and a political commitment — not academic competence. Under such conditions, few qualified black professors will want to teach in black-studies programs, not simply because their academic freedom will be curtailed by their obligation to adhere to the revolutionary “line” of the moment, but because their professional status will be threatened by their association with programs of such inferior quality.

Black students are also forsaking the opportunity to get an education. They appear to be giving little thought to the problem of teaching or learning those technical skills that all students must acquire if they are to be effective in their careers. We have here simply another example of the pursuit of a symbolic victory where a real victory seems to difficult to achieve.

It is easier for a student to alter his behavior and his appearance than to improve the quality of his mind. If engineering requires too much concentration, then why not a course in soul music? If Plato is “irrelevant” and difficult, the student can read Malcolm X instead. Class will be a soothing, comfortable experience, somewhat like watching television. Moreover, one’s image will be militant and, therefore, acceptable by current college standards. Yet one will have learned nothing, and the fragile sense of security developed in the protective environment of college will be cracked when exposed to the reality of competition in the world.

Rustin wrote this in 1970. Back then, many in the Civil Rights Movement and on the political left felt similar to Rustin: promoting ethnic chauvinism or racial set asides does little to solve the big problems in any ethnic community let alone the wider country. Today, this seems like something only Marxists and conservatives argue, as much of the progressive left has ceded the field to critical theory and DEI fixation.

(A lot of popular press treatment of Rustin is fixated on the fact that he was gay and ignores all of his critiques of post-Civil Rights progressives, something I imagine he would’ve seen as validating his critiques of skin-deep, sectarian liberalism.)

Downsizing DEI is doing the left a favor

In the summer of 2020, I was living in Northern Virginia. The local schools were closed. Kids were at home going through Zoom school, which often wasn’t school at all.

Yet as our schools stayed shuttered and vulnerable kids weren’t getting the services they needed in a brick and mortar building, Fairfax County Schools decided to pay “anti-racism” scholar Ibram X. Kendi $20,000 for a virtual presentation about “how to cultivate an anti-racist school community.” It cost $300 a minute.

What was the purpose of paying Kendi this money? Did he improve the school climate in any measurable way? Was giving him $20,000 more worth it than paying for high-quality, high-dose tutoring to at-risk and underperforming kids? (As a long-time tutor, I can toot my own horn and say that I doubt it.)

If you squint really hard, I’m sure you can find some programming somewhere in this country from that summer that actually benefited poor and underprivileged people of any color. But so much of what came out of that moment was like this, where the CEO of American Airlines, Doug Parker, carried around the Robin DiAngelo book White Fragility, which is basically a long rant about how white people have prejudicial attitudes that they can never escape.

Parker had been the subject of an angry missive from the Transport Workers Union of America a few years prior, who were upset that the firm had been outsourcing jobs to overseas countries.

What do you think the chances are that Parker would be happy to read White Fragility but not say, Nickel and Dimed, Barbara Ehrenreich’s famed book about low-wage work?

There’s a reason that everyone from corporate CEOs to the leaders of elite school districts like Fairfax were so comfortable embracing Kendi and DiAngelo. Nothing these anti-racist writers said or did actually threatened the power structure in America.

Diversity politics has long been an elite project — a way for major corporations or government offices to whitewash themselves with a few token hires or irrelevant seminars or programs that send the signal to America’s liberals that they’re on the Right Side of History. But there’s a reason that almost every Fortune 500 company in America was blasting out diversity messaging during the summer of 2020 and not, say, putting their lobbying muscle into passing universal paid leave, guaranteed health care, or decent housing for everyone. Diversity politics has given them a way to painlessly massage the consciences of liberal America without upsetting the power structure at all.

Which is why Trump’s war on DEI, whatever the motivations and whatever the collateral damage, is actually doing the left a favor. For too long, well-meaning progressives have wrongly believed that diversity was the goal of the civil rights movement.

King really meant it when he said he didn’t want people to be judged by the color of their skin, and he went much further in one 1961 document. He argued instead that thinking about each other through the lens of race itself would eventually disappear.

“As the color differential fades," he wrote, "so will the racial point of view. Less and less will it be possible to speak with accuracy of Negro newspapers, Negro churches or the Negro vote. More and more, economic, social, and professional status will be more decisive in determining a man's orientation than the color of his skin."

DEI, on the other hand, has done little more than reinforcing surface-level characteristics. We’re thinking less about the mind or soul of a person and whether they’re black or gay or disabled so that we can slot them into categories and a Fortune 500 CEO can assure is that they’re woke because they have a few people who fall into those camps in the board room.

But this isn’t what the civil rights movement was fighting for. Much of that movement’s goals are still left unfinished. We have no universal health care in this country. We don’t have decent jobs or housing for everyone in this country. The schools that are responsible for educating many low-income African Americans and other minorities are a mess. And no number of DEI offices or initiatives will ensure these problems are fixed.

So maybe Trump and the conservative movement are doing progressives a favor by downsizing these mostly useless programs. It’s time for the left to let them go, because they have no basis in what they’ve historically wanted to achieve in society.

For the rest of my life I don’t know if I can ever forgive the people who made HR departments, drag performers, and racial grievance book writing millionaires the vanguard of the left now.

In the workplace I want more profit share for workers, better benefits, sick time, and maybe just maybe a piece of ownership of “means of production”. Being made a captive audience so capitalists and managers can preach morality to you, the unwashed worker pleb is not any form of leftism I ever ascribed to and it makes it much harder to identify with the label anymore.

I would say in my professional experience, the DEI efforts have had little positive impact on my workplace. I work in a very progressive company so it was already very diverse, accommodating to different needs, and they generally treat you well. One drawback is that there is no paid sick leave. You have to use your PTO, which is common in the private sector. There are constant complaints about this lack of benefit since it encourages people to work while sick (who wants to give up their vacation?).

The problem is that we are owned by a much larger firm that does not want sick leave. But that firm is ok with us having a bloated DEI team that does not produce much of anything except encouraging us not to use certain words and have yearly training sessions done by outside consultants for people that really don’t need it.